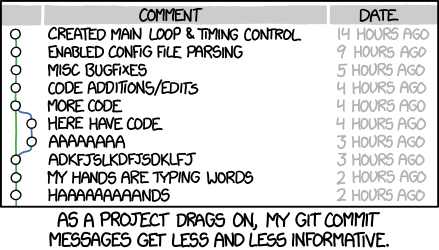

Lately, I’ve been playing with Git and trying to fix a couple of size problem with more or less luck. Git, is a wonderful tool to track and follow changes in almost any kind of document/s or project, specially is they are plain text documents —or sort of— like any kind of source code is. Problem is, code isn’t always alone and oftentimes it goes in company with other files. Mostly binary files that the code uses or produces. Those files can still be tracked with Git, but Git usually can’t see through them since they aren’t text. So, you only know that the file has changed and you record the whole size changing

In other cases, you are a little bit clumsy or inexperience with Git —like me— and you commit files that are too big for GitHub —more that 100mb— so when you want to push the changes to GitHub you can’t.

Measuring your repoPermalink

I think the first thing before we start reducing the size of our repo is measuring the real size of it and try to find out where is the problem. For that we can use a tool called git-sizer and it’s going to give us a report of why our repo is so big. To install it:

1

brew install git-sizer

Then, you go got the root of your repo and you can type:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

git-sizer --verbose

Processing blobs: 7865

Processing trees: 7315

Processing commits: 2974

Matching commits to trees: 2974

Processing annotated tags: 96

Processing references: 115

| Name | Value | Level of concern |

| ---------------------------- | --------- | ------------------------------ |

| Overall repository size | | |

| * Commits | | |

| * Count | 2.97 k | |

| * Total size | 1.16 MiB | |

| * Trees | | |

| * Count | 7.32 k | |

| * Total size | 5.17 MiB | |

| * Total tree entries | 131 k | |

| * Blobs | | |

| * Count | 7.87 k | |

| * Total size | 281 MiB | |

| * Annotated tags | | |

| * Count | 96 | |

| * References | | |

| * Count | 115 | |

| | | |

| Biggest objects | | |

| * Commits | | |

| * Maximum size [1] | 11.2 KiB | |

| * Maximum parents [2] | 2 | |

| * Trees | | |

| * Maximum entries [3] | 573 | |

| * Blobs | | |

| * Maximum size [4] | 10.4 MiB | * |

| | | |

| History structure | | |

| * Maximum history depth | 1.99 k | |

| * Maximum tag depth [5] | 1 | |

| | | |

| Biggest checkouts | | |

| * Number of directories [6] | 104 | |

| * Maximum path depth [6] | 9 | |

| * Maximum path length [7] | 105 B | * |

| * Number of files [8] | 1.90 k | |

| * Total size of files [8] | 177 MiB | |

| * Number of symlinks | 0 | |

| * Number of submodules | 0 | |

and you will get something similar to that one…

Now, you know that the problem is your blobs most of the weight of your repo.

When you commit files too big for GitHubPermalink

I think this is the most common case, when you are beginning with Git and even more with GitHub. You are happily committing your changes with Git and when you want to push them to GitHub to share your repo or to have a backup of it, you come across a message saying that some files are too fat for GitHub and you can’t upload.

Well, this is more or less easy to fix and you can use two tools to do so. One is an “in house” tool that’s called git-filter-branch. The other one is an external tool that everybody says it’s easier to use and more effective, BFG Repo-Cleaner. I decided to use the latter one since it seems simpler, faster and easy to use.

You can find more detailed instruction in the BFG Repo-Cleaner website, but this is more or less what I’ve done. First, I installed the tool in my machine.

1

brew install bgf

Then… I cloned my repo, so I have a backup copy in case something go South.

Be careful: do a copy of your repo before you work with and keep that copy until you are really sure everything work as intended.

Now, I went to root of my repo — you can also perform the command form outside— and run the following command that deleted all the blobs from the commits of my repo bigger than 100 Megabytes.

1

bfg -b 100M [some-big-repo.git]

* You need to add the last part if you are outside the repo

BFG doens’t really delete the blobs from the repo, just from the commits. So after I ran BFG I need to do housekeeping in the repo with the following commands.

1

git reflog expire --expire=now --all && git gc --prune=now --aggressive

reflog command manage the references log and gc clean your repo of unnecessary stuff —garbage collector.

Now, is when I noticed the decrease in size in the repo and I can push changes. However, we have to take into account a couple of things before pushing.

- If you have follow the BFG website steps you probably have cloned you repo from some online repository, and now you can

push.

- If you don’t, you are going to get message something like you first have to

pulland then you are going topush. You can use-fto force the push if you want.

- This happens basically because when you are using BFG you are rewriting your history and in consequence you’re changing the hash of your commits, so they don’t match anymore with the commits in your online repo. In other words, you need to ditch everything you have upstream and upload your repo as it was new. For these reason you need to use

—forceto upload.

- This will have consequences if you are sharing your repo with other users or if you have merge your repo with other repos.

Again![]() be careful

be careful![]() : save a copy of your previous work till you know everything work properly. If you are working with other people in the same repo, notify them of the drastic changes before you begin to work with BGF.

: save a copy of your previous work till you know everything work properly. If you are working with other people in the same repo, notify them of the drastic changes before you begin to work with BGF.

BFG when you’ve merged with an upstream repo that you don’t control or ownPermalink

I’m going to put as example what I’ve done with the repo of this blog. I didn’t have a lot of experience with Git —and I still don’t, living and learning— and I was sometimes just trying things here and here —the stuff of science, test things. The result has been a a little bit clutter Git history to what you have to add that I’ve moved my images a couple of times till I settle with a location I like. I also optimized them with an app, so the end result is, I have in my tree those images committed perhaps a minimum of couple of times, and sometimes three or four times.

The original repo of the template has around ~70mb is size and my repo reached around ~500mb on my hard drive and around ~230mb in GitHub. I’ve made changes and added photos, but not that much to such a bit size.

As I told you, when I started this blog, my use of Git was a little bit rudimentary and didn’t used branches properly, committed a lot in the master branch and other stupidities. I was putting patches and trying things, and I even some time, I think, I duplicated all my history and fixed it somehow… Summing up, no sleep stories, that almost all of us have suffered when you are learning the ropes of a new tool.

On top of all of that, I wanted to continue to receive updates of the template from his creator, so at some point I set up a branch which upstream was the master of minimal mistakes template. Usually my workflow was:

pull the changes → merge to my develop branch → check everything is to my liking → merge to master

This setup gives me total control about what is updated in the template and how, while I still receive updates. It’s a little bit more manual than have the gem

So, I run BFG in this repo in a aggressive way, looking to remove everything over 500K and even deleting all the image files in the folder /assets.

1

2

3

bfg -b 500K

bfg -D "*.{jpg,jpeg,png}"

bfg --delete-folders "assets"

The result was gorgeous. I really trimmed the size to what I have to be —around ~140mb.

The problemPermalink

The problem doing this was… I unrelated the histories of my repo with the minimal mistakes repo, in other words I have to --alow-unrelated as I did the first time I wanted to merge them again

--allow-unrelated— all the changes where reapplied and all the commits from that branch appeared duplicated in my history SolutionPermalink

Sorry, but there is not a correct solution here. Or at least I don’t know one —if anyone nows, please share it with me. If you change the hash of a commit in your history that it comes from a merge and you want to merge again that branch —because there is new changes— Git isn’t going to identify those two commits as the same and they are going to be “duplicated”

What did I do? Clean slatePermalink

Since my aim here was to reduce the size of my repo, but this duplication didn’t satisfy me, I decided to take a drastic measure. I just recloned minimal mistakes repo on my hard drive and this time I created a new branch for my changes. I rename the original branch and rename my branch as master. Copy & paste my changes from my original repo, so all my previous changes are now condensed in one commit. Them push everything to my upstream repo in GitHub. Since I have a copy of my original repo —before using BFG— I considered that as my archive and I’ve uploaded as so.

My repo folder weights now ~170mb with all its branches —including minimal mistakes one with all its changes— which is more than reasonable.

Lesson learnedPermalink

The lesson here is, you can do whatever you want with your repo on the condition you are the owner and the master of all the branches. If you don’t, you have to be really careful changing commits down to your tree because it’s going to be problematic.

You also have to try to adhere to Git best practices and try to keep a working tree as clean as possible. And, of course, be mindful when you add those binary files or do not add them at all unless they are really necessary.

There are also other options when you have to work with big files in Git, like LFS, which I have yet to explore.

-

This is not really true isfyou use some Git GUIs or Diff tools that can show you the two different versions of the file, but in the end you are going to to end with the two versions stored somewhere else. Also, depending in the type of file, Git will be able to store just the differences of the file, since it’s stored in text mode, but best practices always tell you that you shouldn’t track those files with Git, even more if your code are the one generating the file. For example, if you have a markdown code that generates a pdf file, you store and track just the markdown not the pdf. ↩

-

I have to confess that till really recently I was using the gem and the whole code of the template at the same time. It didn’t have any downside, but it wasn’t really smart. ↩

-

You are probably thinking: didn’t you make a branch to begin with you changes form the original template?. NO!

I didn’t. I just delete all the stuff I didn’t wanted and then I begin to edit the template. After I changed to upstream repository of master to the curren repository —actually I was messing even more for sake of curiosity, but for the sake of everyone let’s keep this short— and uploaded my changes. After that, I realized I wanted updates and after more messing, so on an so forth, I ended with a branch with the upstream to minimal mistakes master. ↩

I didn’t. I just delete all the stuff I didn’t wanted and then I begin to edit the template. After I changed to upstream repository of master to the curren repository —actually I was messing even more for sake of curiosity, but for the sake of everyone let’s keep this short— and uploaded my changes. After that, I realized I wanted updates and after more messing, so on an so forth, I ended with a branch with the upstream to minimal mistakes master. ↩ -

They aren’t really duplicated, unless you rebase. However, when you merge, all the commits of that branch become part of your history. They are the parents of your following commits. If Git thinks that they aren’t the same commits as before, you’ll see them duplicated in your history

. ↩

. ↩

Leave a comment